WRITTEN BY: Lexus Morrow

Today, and all of February, is set aside to honor and remember the rich and deep history of Blacks and African-Americans in the United States.

Communities worldwide are in a time of turmoil and pain while enduring systems of racial inequity that persist to this day. But this month is not just about understanding and remembering African American ancestors’ pain and harsh experiences but rejoicing in their remarkable feats and accomplishments. We celebrate Black History Month as a way to hold onto the truth that, even in the darkest moments, truly great things are possible.

This month at Outdoor Outreach, we celebrate Black history by exploring the significant achievements of Black folks in the outdoors and the footprints they have left everywhere.

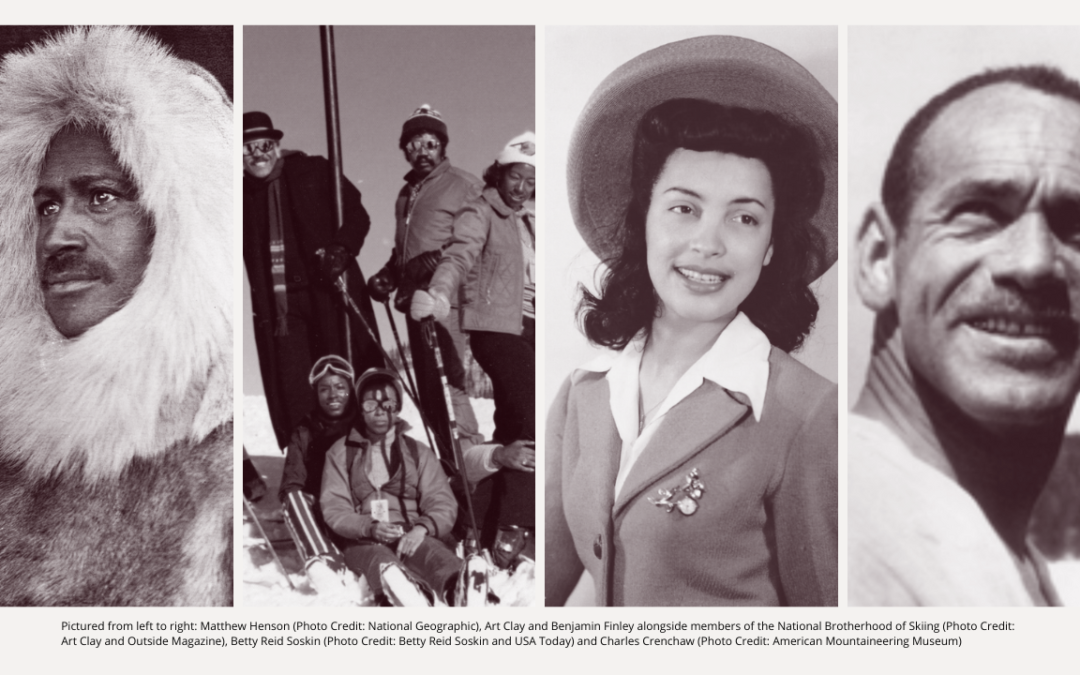

Charles Crenchaw

On July 9, 1964, at 1:30 pm, the first high altitude radiotelephone transmission was made. The first Black American mountaineer, Charles Crenchaw, reached the top of Denali–the highest point in North America. The expedition included Charles Crenchaw, Frances & Al Randall, Chuck DeHart, Pat Chamay, Norman Benton, and more. But it was Charles, the only African-American in the expedition, that made history.

The group camped until July 12, and once the weather permitted, they trekked down the mountain and headed home. Crenchaw described his descent from the top of Denali as “like going through the gates of hell.” After this climb, Crenchaw went onto climb many more mountains and even served on the board of directors of the American Alpine Club for many years. Crenchaw would not be the last African American to scale the treacherous mountain, nor was he the first to try. What must be noted in our memories is that he was the first to succeed.

Matthew Henson

Another African-American feat hidden from history was Matthew Henson’s trek across the ocean. Matthew Henson was born in Maryland one year after the end of theCivil War. As one of the first generations to not be born as a slave, Henson’s life became about exploration, adventure, and the call of discovery.

Though forgotten and dismissed in history, his legacy would be the stepping stone for all theexplorers who would follow. He would spend most of his life as a sailor traveling the seas, eventually leading him to meet Robert Peary — the leader of the North Pole expedition.

Henson poses with three Inuit team members and a sled dog during an overland crossing of the Arctic. PHOTOGRAPH BY ROBERT E. PEARY, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

“The lure of the arctic is tugging at my heart. To me, the trail is calling! The old trail, the trail that is always new.” – Matthew Henson

The final North Pole expedition group had whittled down from 24 to just Matthew Henson, Robert Peary, and 4 Inuit Natives: Ooqueah, Ootah, Egingwah, and Seegloo. On the morning of April 9, 1909, when backtracking, Henson saw the footprints and realized that he had made the first steps in history at the North Pole. Unfortunately, due to racism and discrimination, Peary was recognized for the discovery, and it wouldn’t be until 1937 that Henson would receive the recognition he deserved. On the 79th anniversary of his discovery, Henson received posthumous full military honors, and his gravesite was moved to Arlington National Cemetery near the monument of Robert Peary.

Peary agreed that the expedition would only have been accomplished with his trusted friend. “Henson must go all the way,” he said as they planned the trip months earlier. “I can’t make it there without him.”

Benjamin Finley and Arthur “Art” Clay

Two individuals who made a more recent impression in outdoor history are Benjamin Finley and Arthur “Art” Clay; the founders of the National Brotherhood of Skiing. Finley and Clay organized the first convention of 13 African American ski clubs from around the county with 350 attendees in 1973. This would be the first, of many, biennial Black Summits and the National Brotherhood of Skiers (NBS).

In the 1970s, there was a very small population of Black folks that skied or snowboarded, and it was Finley and Clay’s goal to increase the black skiing population. And it surely made an impact: the NBS has seen and cultivated 10,000+ black skiers, and today offers a prestigious scholarship for young athletes so they may attend the Burke Mountain Academy — a ski school in Vermont. Because of their history-making efforts with the NBS, they were inducted into the US Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame in 2019, making history a second time for being the first Black inductees.

Betty Reid Soskin

Betty Reid Soskin is another name who made history recently, or as she would say, Herstory. Soskin retired from the National Park Service (NPS) in 2022, at age 100 years old, making her the oldest National Park Service Ranger. She worked as an NPS Ranger who tirelessly promoted and raised the voices of African Americans and women of color, specifically those who were involved in World War II. Soskin started working at Richmond National Park during its creation in 2000, and like many African American pioneers, she usually found herself as the only person of color in the room. Not only is she the oldest African American NPA Ranger, but she and her husband founded one of the first black-owned music stores in the California Bay Area. She’s been named Glamour’s and California’s Woman of the Year, has met Barack Obama, visited the White House, and even had a middle school named after her

“I feel such pride in the uniform,” Soskin told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2018. “When I’m in a public place, I’m announcing silently to every child of color a career path that they might not ever be aware of, because they’ve never seen a person of color like me in a National Park uniform. And the possibilities that I am making that announcement silently is so empowering, both for me and those children.”

Finally, beyond honorable mentions are the vast impact that the unsung African-Americans and Black heroes had within National Parks — even before they were named National Parks.

- The Buffalo Soldiers and Colonel Charles Young, a Brigadier General of the Buffalo Soldiers (and the first African-American National Park System superintendent) helped save historical spaces like Sequoia and Yosemite National Park. Considered the first park rangers, these individuals deterred poachers and thieves while fighting fires that threatened these fantastic landmarks. This occurred during a time when their parents were not afforded full-class citizenship, and there was very little democracy, liberty, or equality for African Americans in the United States.

- Stephen Bishop, a former slave, was credited with discovering and exploring many caverns at Mammoth Caves National Park in central Kentucky. Even before the start of the Civil War, he led tourists on excursions, where he created the first maps and named many of its most recognizable features.

- Lancelot Jones was an African-American fishing guide and entrepreneur instrumental in founding Florida’s Biscayne National Park. He used the land his father gave him to create the fishing service. And when developers attempted to buy the surrounding land to build a resort community, Jones fought against them. His resistance helped rally support for the park to become a National Monument in the 60s and eventually a National Park in 1980.

“To inspire lasting connections, people need to see their history and culture represented in our nation’s national parks and monuments,” says National Park Service chief historian Turkiya Lowe, the first woman and the first Black American to hold that position.

At Outdoor Outreach, many of the youth we work with come from communities of color that have been historically excluded from outdoor spaces. We know that nature-based recreation is critical for community health and that representation and a sense of belonging in the outdoors matters.

While many of the accomplishments above were not acknowledged or celebrated for many decades, we are proud to share these stories with our youth today so they know that people just like them can be the first to accomplish great things —especially in the great outdoors. We encourage you to continue learning about these brave and notable outdoor enthusiasts and share their stories.